Hear O Israel! On the Trail of Herbie's Lost Masterpiece

On the re-release of Herbie Hancock's epic forgotten gem

A 20 minute read

Jewish Quarterly Autumn 2008

Once, in the mid-60s, Herbie Hancock was brought into a suburban synagogue project to make the Shma swing harder than it ever had before. Lemez Lovas goes on the trail of one of the most intriguing Jewish albums of all time.

I like a lot of movie music, and of course the masters are Jewish songwriters, really. And I always find it quite interesting when you’ve got people like Anthony Newly, and Leslie Brickers, who when they started out they called themselves Brickman and Newberg to sound more Jewish even though they weren’t, just to get more attention, or a bit more trust. I mean, they’re great songwriters anyway, but, you know, the Jewish songwriters are the masters. The Sherman Brothers are possibly my favourite. They wrote a large majority of the music for Disney back in the Golden Era of Disney, so a lot of the recordings from The Jungle Book, a lot of the recordings from Mary Poppins is theirs: fantastically clever lyrics, great patterns, just brilliant music, really. That’s my favorite, really, that sort of classic Jewish songwriters. They’re just masters, master of the art and the craft. I don’t think anyone else gets close.

Sherman Brothers singing with Walt Disney

Retro music king Jonny Trunk is sitting in a garden café near his North London home in Stoke Newington doing what he does best – talking excitedly about obscure recordings. Trunk is a particularly English kind of hero: a bespectacled, mild-mannered, good-humoured anorak with a cheeky past and passion for the unusual. In American slang, he could been called a ‘foamer’: a trainspotter who gets so excited by a sighting of a rare locomotive that they start foaming at the mouth, unable to hold their pencil straight. Luckily for us, it is not trains that get him all steamed up, but music: Trunk is part of that very select breed of cultural trainspotters, the obsessive record collector.

As someone whose parents once offered to take him for professional help in order to help him overcome his own black plastic disorder, I can testify that the railway enthusiast and vinyl junkie are brothers in compulsion: sifting through archives in the pursuit of arcane information; meeting furtively on seedy suburban bridges to exchange battered goods; trading conquests and consolation in the darkest recesses of the web. Record collectors, like train cranks, guard their hard fought collections jealously, but thankfully Jonny Trunk’s mission is quite different, and he has spent the last thirteen years making rare and wonderful recordings available again for a wider audience on his Trunk Records label.

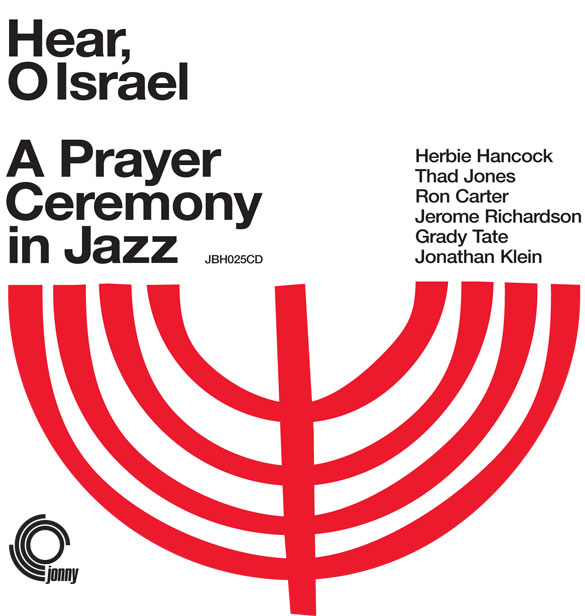

His latest offering is almost too good to be true: Hear O Israel: A Prayer Ceremony in Jazz – a 1968 recording of Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and a stellar cast of late 60s jazz musicians swinging along to a hip arrangement of a Friday night shabbat service. There are some Jewish records out there by famous non-Jews – like the homage to the great Yiddish klezmer comedy king “Don Byron Plays the Music of Mickey Katz” – but the music is rarely that Jewish or the musicians that famous. Hear O Israel is unashamedly both of those things: and the effect is quite startling.

From the first angular piano chords of the ‘Blessing Over the Candles’ until the last swirling cascade of horns and voices on the ‘Final Amen’, this is unlike any other Friday night service in history. On ‘Kiddush’, the laid-back bossa nova beat and soaring flute melody laces the Palwins with a shot of cachaça; ‘The Shma’ is transformed into a six minute spiritual jazz workout, opening with slow meditative piano and baritone sax before the drummer picks up a fast bop groove and works the band into a swinging frenzy, trumpet and alto sax firing out hallelujahs on high like zoot-suited cherubs sweating it out at a late night celestial lock-in. “Praise him with the blast of the horn, praise him with the clanging cymbals, let everything that has breath praise the Lord,” intones the solemn voice on ‘Final Amen’: as the rabbi reads out the declamatory, triumphant psalm on the last song, the band join in one by one – first piano, then brushed drums, then the horns, and finally the singers, all joining together with eyes and ears turned upwards. Amen, Amen, Amen.

I first came across the record in the late ‘90s, through a guy called John Cooper who, in recording collecting circles is a bit of a strange character in that he has a vast knowledge of very obscure records. He lent it to me briefly and that was that. Then two and a half years ago I was thinking of setting up a website just dedicated to what they call orphan works, which are lost recordings – recordings whose owners can’t be traced – and I borrowed it again from John Cooper, and when I listened to it, I had this extraordinary physical reaction that I haven’t experienced before. It just sort of took me to another level, mentally. And almost physically, actually. As soon as it started I just thought it was extraordinary. It’s a bit of an overused word, especially in jazz circles, but extremely spiritual. I felt almost sort of strangely touched by it. It was very odd. And so I started investigating it.

With scant details to go on, Trunk discovered that the recording was owned by the Union for Reform Judaism, who had commissioned in the 1960s from a rabbi from Worcester, Massachusetts, and a teenage composer called Jonathan Klein.

An ethereal liturgical piece from the Who's Who

The music Klein composed is a adaptation of a Friday night service arranged for jazz sextet with two singers and a male reader, couched in a late 60s, modal jazz idiom, complete with furious solos and angular female voices darting about high above the fray. What is remarkable about this recording is not so much how it sounds, but quite how it came to pass that one of the world’s most famous jazz musicians – without any documented relation to Judaism – went to a studio to record versions of the Sh’ma and Kiddush in the first place.

I think what happened is that a rabbi called David Davis in the mid-60s had thought to spice up the Friday night prayer service, to bring a new crowd down to the synagogue using jazz. I don’t know how he knew Jonathan Klein, but he got this young, extremely talented 16 year old to write the prayer ceremony out in a jazz form. They performed it, it did very well, and I think they did a mini tour with a travelling band in various synagogues around New York State, and then in mid-1968, David Davis said, look, it’s gone very well, why don’t we do what most people do in this situation, and make a record of it? And this is where it gets foggy because I don’t know how a Jewish organization making a recording about a Friday night prayer ceremony happened to bring in pretty much the best jazz musicians in the world, at the time. All the people [on the record] were major, major, major performers and artists. They are the cream of the crop, really, and those people stretch across all great jazz recordings in America over that decade and the following decade. I mean, it’s extraordinary. That’s what I find a bit of a mystery, because it’s not something where you just pick up the phone and go, hi, is the Herbie Hancock Quintet about? I mean, I just don’t understand. I advise you to track down Rabbi David Davis: I think he holds the key to acquiring all this information.

Jonathan Klein at the time of his dream gig.

Jonathan Klein at the time of his dream gig.

What makes this album so compelling is that its premise – the jazz service – seems to have been at the forefront of the modern movement to make synagogue culture hip to young Jews who would rather be out dancing than in davening on a Friday night. The great liturgical revolutionary, Shlomo Carlebach “the Singing Rabbi”, was taking his yeshiva folk to the masses in exactly the same period, but while Carlebach was a prolific spiritual songwriter, he was no great musician. Herbie Hancock, on the other hand, is another story.

Another Jewish jazz spiritual epic from the period

When I finally manage to catch Rabbi David Davis on the telephone from his West coast home one Friday morning, he sets about filling in some intriguing gaps.

“Like most things that you think will be complicated,” he says with a laconic drawl, “in fact it was rather simple."

I took a position in Worcester, Massachusetts as an assistant rabbi to a very large congregation, with over fifteen hundred families. The senior rabbi was a man named Joseph Klein – Jonathan was his son. He had an extensive musical background: Joseph was a cantor and had one of the largest private collections of opera records in the country. In the meantime this was the 1960s, the period of love, festivals, young people carrying guitars and exploring what they could do with music, and they used to come to my office after school – at the time I was 28 years old, about ten years older than they were. I felt that the old music was old music and the kids weren’t coming [to shul], and I decided to try to see if we could play contemporary music and lure them into the temple. So I asked Jonathan, who was an extremely talented 17 or 18 yr old, to research it and see what he could come up with.”

His musical project to entice young people back to the empty synagogue met with some initial resistance from an unlikely quarter.

The first hurdle we had was trying to convince his father, the rabbi. He was a reform rabbi, or what you might call a liberal one in the UK – but his own father was an orthodox hazan, so Joseph himself was really one step away from orthodoxy. He used to say to me, “David, you can try whatever you want, just keep the kids and guitars away from me!” But this idea, he really thought it would be a shanda… “How can you do something like this in the synagogue?” Well the synagogue seated a thousand people and we filled every seat. Usually for a sermon he would get seventy five at most, so when he saw his assistant and kid get a thousand he didn’t know what to think.

The teen sensation Jonathan Klein and his band then rolled out concerts in synagogues across the New England area, with a changing line-up every time: “We couldn’t always bring our talent from Worcester,” recalls Davis, “so we had to pick up kid talent locally.”

The recording sessions themselves came about when Davis left Worcester and went to New York to work for the youth movement of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, who were looking for a project to sponsor. “The guy I worked for was a music fan, and I told him we had this number that we just did that really took New England by storm. We had a little extra money, and the record producer that he hired knew Herbie Hancock and the crew of guys you hear on the record – major league guys. On the record it’s them plus a seventeen year old kid and a twenty eight year old rabbi trying to knock it out with these guys.”

Even Tom Jones was getting in on the act.

Sadly, what Davis has to say about the session doesn’t reveal anything juicy like an explosive story about Hancock’s secret conversion to Judaism. The mechanics of it were all quite banal: “To use their language, I guess they were between gigs. We did the whole thing in two sessions; they weren’t too many takes, they seemed to study the music like you would study for a quiz before they picked up their instruments. They were warm guys, very professional.”

After the recording, the UAHC pressed a thousand copies, which they distributed privately, and soon the album fell into obscurity. And as for Jonathan Klein, the teen jazz sensation who performs on French horn and baritone sax alongside these heavyweight legends, Rabbi Davis’s eye for talent was proved right. Klein is now a professor of composition for film at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston.

Klein himself doesn’t remember a great deal about the session, namely due to his own nerves as he was playing with the big stars that day too: “I remember we recorded it in a two track studio, not the multi-track recording that I was hoping for. It was a big day but I was too worried about my own laying to pay much attention to what else was going on.”

His feelings about the re-release of his first ever recording – a forgotten gem with an allstar cast – are surprisingly to say the least.

“Jonny Trunk sent me a couple of CDs but I haven’t opened them,” he says down the line from his Massachusetts home. “The reason is that, well… this is quite a difficult situation for me. It was not put out with my blessing: I never wanted it reissued and I kind of hoped it would never happen.”

The reasons for his reticence are more to do with embarrassment at the fruits of his teenage mind than anything else: “I was aged nineteen, and had something in my head that I just couldn’t get out properly. In terms of how it came out musically: I hoped at the time it would be better – mainly in terms of the quality of recording, the arrangement and the type of singers. Someone booked opera singers, and I just went along with it: I mean they were great but in no way appropriate for jazz. I think it’s unlistenable.”

Another version of the piece that Klein says is “a lot better in terms of the writing and arrangement,” this time recorded by Berklee students and staff, will be released as part of the Milken Archive of American Jewish Music series in February 2009 with the out-takes of Hancock’s solos from the 1967 recording. There are even plans afoot in London’s hyperactive Jewish Community Centre to recreate the original concerts in a synagogue setting with the hotly-tipped American Israeli pianist Omer Klein.

Back in Stoke Newington, Jonny Trunk is wondering whether it would be worth interviewing Herbie Hancock for this piece (for the record he was unavailable at the time of asking). “He’s sat in so many sessions, and he’s been on so many records, that it must all blur,” muses Trunk. “Although this one is slightly unusual, isn’t it? It’s a Jewish prayer ceremony – that doesn’t come up every day, does it? I think he must have some kind of recollection, and his piano playing is very good on it.”

His reticence over whether we should contact him directly or not is understandable: “Herbie hasn’t been in touch, but his lawyers have!” he laughs. “They were wondering what on earth the recording is and what it’s doing out in the world. There’s a part of me that’s always feared such enormously important jazz people because if they’re in the wrong mood they can quite easily go – even though legally the recording is absolutely correct – ‘I don’t like it, can you withdraw it from sale?’ They can find out all sorts of reasons, do you know what I mean? Again, I think with a lot of these people it depends on which way the wind’s blowing. It’s a great thing… I’m sure he’d probably quite like to hear it.”

Trunk would love to share the music with his Ultra Orthodox neighbours in North London, and his one man local advocacy initiatives might be paying off after some initial minor blunders.

I went out Saturday morning a few weeks ago, and saw a Hasid and his son standing outside my house. I ran back in, got a CD, and said, “Can I give you this?” And he went, “I’m sorry, I can’t hold anything. It’s the Sabbath.” I said, “Can you put it in your pocket?” And he goes, “No, I can’t hold anything today. I don’t carry today.” I just explained to them what it was, and they asked me to come to the synagogue and talk about it and explain it. “Come play it to us.” And I’m getting really excited. And the son’s going, “Wow, cool.” This is exactly what I want. I was thinking I should find a store up in Stamford Hill to sell it, you know? I know that it’s risky: the music is kind of tampering with stuff that I’d imagine it’s supposed to be set in a certain form. But I don’t know how anyone can fail to appreciate its total beauty: and that’s the sort of sound we’re always pursuing – the sound of true musical beauty. Most record people I know, the only religion they have is black wax.

Hear O Israel: A Prayer Ceremony in Jazz is available in limited edition on LP and CD from www.trunkrecords.com