Improvisation and the Body

A physical method for singing and improvising flawlessly

A 10 minute read

Coltrane on sparkling form in the SoulTrane sessions

I love Carnatic music for many reasons, but the reason that is easiest to explain, and easiest for others to hear, is the way that the masters improvise. When I say improvise, I am not talking about improvisation in the way that I previously thought of it: musicians playing notes. I used to play jazz, and went to workshops on improvisation, where the emphasis was on self-expression. The Carnatic way of improvisation is different altogether: the goal of improvisation is to bring about the tiniest nuances in the mode, or raga itself: the musician is a vehicle for the highest expression of beauty that the palette of vibrations that make up the raga can conjure up. It is less about expressing yourself, and more about expressing that which is inexpressible. It is less about the musician, and more about getting to the greatest heights possible in a particular mood.

A typical jazz woodshedding practice session

Musicians in jazz often improvise fast - especially so since many of them follow John Coltrane, known for his phenomenal ‘sheets of sound’ technique. In the worst cases, playing fast can become a goal in and of itself, a display of pure technique with no regard for how musical or not it may sound. The technical skills on display are honed by years of ‘woodshedding’ - practising flurries of notes, chord structures and phrase patterns ad infinitum.

Carnatic music is a different beast entirely. The masters have much less to work with. Firstly, the mood in jazz is created by its shifting chord patterns, and good solos are built by creating rhythmic patterns of tension and release around these changing chords. Carnatic music has no chords at all - just one mode, or raga, that evokes a particular mood. Where jazz musicians can create tension by playing ‘out’ of the scale, and carve out a release by going back ‘in’, Carnatic musicians only play ‘in’.

Where jazz musicians often work with complex chords, where every note both in the chord and around it are available for improvisation in an order, Carnatic musicians are limited to allowable sequences of notes, which often changing depending on whether the phrase is going up or down. Jazz chords often cram clusters of notes together in dissonance: many ragas distinguish themselves by emitting key notes in a scale. Within a single phrase, on a single chord, a jazz musician may allow themselves to explore all twelve semitones, either as held notes or in passing.

In Carnatic, the musicians rarely have more than five or six: half of the available raw material in jazz.

Where jazz adds improvisational possibilities, Carnatic takes them away.

The incomparable Bombay Jayashree

Live concerts generally last from two to three hours, in which the musicians will play just a few different ragas, improvising throughout.

There are two things absolutely astonishing here: 1) with all the limitations discussed above, the musicians can keep your rapt attention with endless invention. I have never experienced time in a concert passing as quickly as in a Carnatic concert: the hours become minutes in the hands of a real master. The improvisational phrases layer on top of one another, higher and higher, without undue repetition or growing stale. 2) the musicians can change from one raga to the next in a heartbeat, flawlessly. Think about this for a second: you must spend an hour improvising with just a few notes at your disposal, and then when the next piece begins, all the notes change, and you must instantly be inside the new space. It is like giving a complex technical lecture in one language for an hour, and then changing to another topic and continuing the lecture in another language. This happens several times during a concert: each time a different topic and language.

Yusef Lateef, The Plum Blossom, from Eastern Sounds

The first point is a marvel of technique and ideation: how musicians can keep your interest for long periods of time with few raw materials. It has been done in jazz: the wonderful modal jazz musician Yusef Lateef plays a five-note Chinese flute on his seminal Eastern Sounds album, and the solo is so fluid and inventive that if it wasn’t pointed out to you, you’d never notice. But his solo lasts a minute and a half: the forty minute improvisations in Carnatic are another thing altogether.

It is the second point that I want to talk about here, particularly in regard to vocalists: how can singers play ‘inside’ a scale, with only a few notes at their disposal? To play ‘out’ would be to play a different raga altogether, and would bring down the wrath of the audience upon the performer’s head. How can they do it at the rapidity of John Coltrane’s sheets of sound, using only their voice, without ever making mistakes in pitch? And even if they can do it for one raga or mood, how can they change raga entirely, and continue at the same level of flawless execution, without a single mistake?

Prodigious levels of technique and concentration are a given. But are there devices that they can use to allow them, not to search for the notes each time, but instead just to locate them?

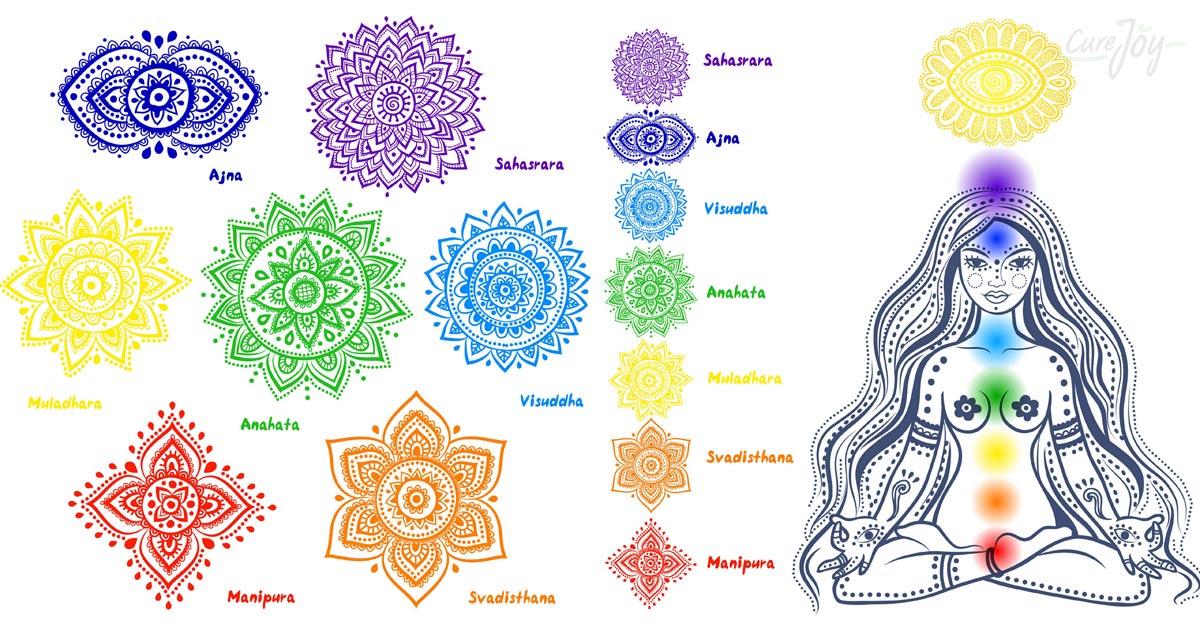

Many Western musical traditions use auralisation - hearing the note before you sing it. It turns out that the key to Carnatic improvisation is not to think about the sound of the notes at all, but to feel them in your body. Tantric tradition has a handy means of doing this: the seven chakras located throughout the body.

| swara | solfege | note | chakra | position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sa | Do | C | Muladhara | under the spine, perineum |

| Ri | Re | C# / D | Svadhishthana | base of the spine, to the rear |

| Ga | Mi | D# / E | Nabhi | stomach |

| Ma | Fa | F / F# | Anahat | chest |

| Pa | Sol | G | Vishuddhi | throat |

| Da | La | G# / A | Agnya | third eye |

| Ni | Ti | Bb / B | Bindu | dip in back of head |

| Sa | Do | C | Sahasrara | crown |

Performers are encouraged not to remember the pitch of each note in a raga, but to feel it as a vibration in each chakra in the body. This can be unnerving at first, but with practice, the note becomes located firmly as primarily a physical feeling, a series of vibrations in the body. When you want to sing a note, you merely reproduce the sensation. It completely transforms practice sessions - instead of listening, you start to seek responses from your whole body. I look forward to coming back to this theme when my practice and improvisational skills are more embedded.