On Music and Healing

Inside the magical, mystical world of sound, healing and great art

A 12 minute read

- blog

- special education

- consciousness

- war

- technology

- music therapy

- healing

- Nigel Osborne

- Pondicherry

- carnatic

- Bosnia

- India

- UK

Nigel Osborne at India's rather fine INKTALKs series

Why does mankind have music? The evidence points to one thing: music exists to make us feel better. It is the most direct and accessible way in which we can heal ourselves. With music, we can change ourselves, transport ourselves. Music therapy is not new. Music is therapy, and has been since the dawn of mankind.

India is the place for gurus, to find teachers who can change your world. Over the past three days, invited quite by chance by my Carnatic teacher, a wonderfully generous singer called Shobha Raghavan, I have met another guru: a person who embodies what I believe music-making and music-thinking should be.

He is a British composer: indeed, “one of Britain’s best kept musical secrets” according to the Guardian, but that is the least interesting thing I can say about him.

Having not heard any of his music, but based purely on listening to him over a couple of days, I have a feeling I would like his creative output. How can I tell? He can sing folk songs in dozens of languages, and have a room full of shy Tamil schoolteachers singing along effortlessly. He is an activist who has been trying to campaign for fairer copyright provisions for new artists, a shitstirrer (I mean that as a great compliment) who has a holistic, reflective view about why music is connection and connection is everything and everything that is important about human beings you can find in music.

Nigel Osborne

Nigel Osborne

He is a superb cheerleader for music’s importance. In a time where it is being derided, mocked as a luxury for the middle-classes thanks to the Cartesian blindness of our blighted rulers, music desperately needs someone to join the dots, loud, in public.

Let us say this now, once and for all: music is far more than entertainment.

Entertain(Eng.) <- Entretenir (Fr.)

- (transitive) to maintain, to look after

- (transitive) to support (e.g a family)

- (transitive, figuratively) to fuel, to keep something going

- (reflexive) to have a discussion (with someone)

- (reflexive) to keep fit

In old French, ‘entretenement’ was literally ‘upkeep’, the thing that kept you going in between. It used to mean a salary - as in the idea of ‘maintenance’ paid to soldiers, but came to mean amusements, the thing with which you keep yourself going from one day of drudgery to the next. It keeps us ‘up’ - without which no doubt we would be down. But music is so much more than that.

Music is an oral record of humanity. All humanity’s ideas are present there, along with all our deepest questions. If we accept that it is an external force that can make us gloriously happy or desperately sad: it follows that, in the DNA of those emotional responses, is our entire cultural history. Why one piece makes us feel one thing and not another - this is not a reaction that we have chosen. It is something that runs deep within the fabric of our existence. The thread that binds a fast drum and a feeling of euphoria is both related to the biochemistry of our bodies, to our internal rhythms, and to our most sacred traditions.

Nigel Osborne’s particular speciality is connection - making music in the now. If it sounds like a yogic practice, it is, but his school is not yoga, but working with children suffering from war trauma.

Nigel letting rip with a fine Bosnian opera singer

Rather than talk about him, I would like to briefly talk about the points he has made, and why I find them so exciting.

The first point is ‘music therapy’. It has several strands - musician as a form of psychiatric therapy; music as medical research via neuroscience and biochemistry; music as social activism, via community music.

Nigel’s approach to the therapeutic strand, working with children with special needs, is what I want to talk about here.

Therapeutic Music Therapy

The music that you can make with ‘special needs’ children should be better than the music you can make with other musicians. It can be the best art anyone has ever made. These children do not have limitations. They have gifts.

Let’s just think about this for a second.

What God (or nature, or whatever you want to call it) takes away, it also gives back in countless measure. Our job as educators is to find out what these children have to give back, and to put that at the centre of the art that they can make. We are not doing this to help us. We are doing it to help ourselves. These children can show us new ideas and new directions for art that our limited minds cannot yet conceive.

If there are brilliant artists working within the special needs environment, this is why. Special needs children can save music. Let me repeat that:

Special needs children can save music.

How? Because special needs children, like adults with dementia, have tremendous advantages over the rest of us:

1) they exist in, and for, the present

2) they are free from the regrets of the past, and the anxieties of the present

3) ego and inhibition doesn’t stop them from doing what they want

4) they experience the world in ways that we often can’t

Therefore, let us not pity the person working with special needs children, but envy them. These children can unlock for artists paths and horizons that would be inaccessible without them.

Music As Medicine

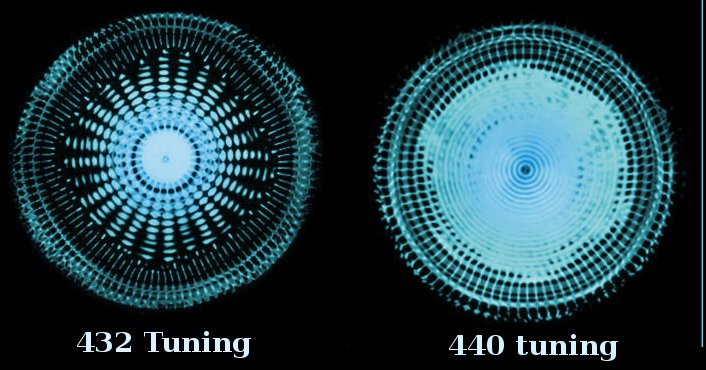

Cymatics at work

Cymatics at work

Cymatics is the visualisation of sound frequencies. Every body comprised of particles has a resonant frequency, including the organs in our body. Nikola Tesla and Vladimir Gavreau carried our pioneering work into infrasound - sounds below the human hearing spectrum - in an effort to create a weapon that could damage human organs internally, only through sound.

That resonance of sound affects our bodies is something that has been known to mankind for a long time. The Natyashatra, the world’s earliest treatise on the arts, suggests the emotional and physical responses that particular combinations of sounds can have. Musical scales and patterns, codified as ragas in Indian music and maqams or dastgah in Turkish, Arabic and Persian music - have long been used for specific medical purposes, both to treat certain illnesses and as therapeutic methods to reduce anxiety and depression.

Science is a useful tool for explaining things to others that you as a musician, instinctively know to be true. It gets you in the door, in places where your feeling alone most certainly won’t.

Sufi musicians at work in Istanbul hospitals today

Sufi musicians at work in Istanbul hospitals today

Doctors in the past clearly knew things that doctors today don’t. The concept of holistic medicine, derided frequently today as ‘new age’, is anything but, as the briefest study of the fathers of modern medicine, Abu Bakr Razi, Ibn Sina and Al Kindi will show. At one point in the late 16th century, it appears that it was decided that music had no role to play in modern medicine - the Cartesian fascism of the modern age, which has no room for anything which empirical science cannot prove - was upon us, and with it, all human knowledge that had been accumulated over the generations but that science had not yet caught up with was lost.

Dementia - the process by which we lose access to parts of our brain - can unsurprisingly show significant improvements when treated with music.

Millenia-old Sama Vedic chanting lighting up the brain like Christmas lights

Thankfully, modern science is catching up slowly. Neuroscience and brain imaging is starting to explain to science what practitioners have known all along: that spiritual music practises can engage the human mind and body in extraordinary ways.

Is it possible that DNA, too, has resonant structures, and that sound waves, carefully focussed, can bring about change on a cellular level? Could music, and music therapy, be the next frontier in modern medicine?

This is where Nigel’s experience of musical work with victims of trauma - complimentary to that of Oliver Sacks, with whom Nigel has worked in Boston - comes in.

He has seen extraordinary proof of music to bring about profound changes in victims of severe trauma and disability. Why should this incredible knowledge remain the domain only of the severely traumatised? If music therapy can change the lives of people whose nervous system has been half-destroyed, imagine what it could do to people who haven’t.